David Dimitri

Poetry on a Tightrope

JANUARY 28, 2025

In 2017, the Greek press spoke in glowing terms about the acrobat who was set to perform at IST.

The photos from the publications filled me with admiration and vertigo. I was 10 years old and wondered if he could even walk on water.

I couldn’t watch the performance because I fell ill with a high fever, which skyrocketed to unimaginable height perhaps because I missed something that those who saw it described as unparalleled and unprecedented.

Much later, I saw the iconic photograph Lunch at the Top of a Skyscraper in New York, with the eleven ironworkers sitting on a steel beam at Rockefeller Plaza. Instantly, Mr. Dimitri came to mind, and in my mind, he became forever linked to them.

The strange thing is that I have never seen one of his performances, yet I have delved so deeply into his work through photos, articles, and interviews that my brain can instantly recall images from many of his acts. And not just images, but emotions as well.

His artistic genius is undeniable.

Even though he offers breathtaking visual spectacles, what you truly take away is something more. He sparks intellectual exploration—somewhat like the feeling you have after watching a film or reading a book. I’m sure I’m not describing it well at all.

As you read what he shared with me, you’ll see that he is someone who moves through multiple dimensions of aesthetics, orchestrated by a philosophy that embraces the beauty of life and a deep love for humanity.

Mr. Dimitri, Maurice Béjart said for your that you have got “The talent of a mad man”(avec un talent fou). You are undoubtedly a fearless man. Is the feeling of fear in you much lower than it is in most people, or have you understood its mechanisms and developed ways of managing it? I also wonder what scares you and what you consider dangerous.

This is an interesting question. Fear exists when things are uncertain. For instance, if I’m standing 60 m above the ground on a thin cable and I’m unprepared for the task, even I would be afraid. But if I’m trained and prepared, then I will feel very comfortable. It’s the same thing if I stood in front of an audience to do a speech, not knowing at all what to talk about. I think I would be just as afraid as if I would when standing unprepared on a high wire. It is the Unknown. As soon as you’re familiar with whatever you’re about to do or the situation, then there is no reason for fear. But the simplest thing could be fearful if your mindset is in a certain state of mind. For example, if I have a character who doesn’t really care what anyone says or thinks about me, then I would probably be less fearful, standing in front of an audience to do a speech without knowing what to say. But if I would be a self-conscious and insecure person, I might be afraid simply by standing at a road crossing.

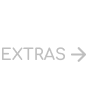

But to come back to my profession and the things I do, walking high up in the air on a thin cable or shooting myself out of a cannon, yes, one could say that I might be less fearful than others. But then again that’s maybe just because I’m so used to doing what I’m doing.

The New York Times described you as the “Lord of the Wire”. Your top moment was when you baptized in the air, the new Frankfurter Waldstadium. The absolute awe was when you crossed on a high wire, a distance of 300m at a height of 70 m

in the city of Pilsen, Czech Republic. What every normal person considers impossible, for you is a routine.

Did something ever go wrong that apparently for the sake of speaking at this moment, you coped with? Have you done crazy things that you will never do again, or have you thought about doing things that, even though you planned them, you abandoned them because of excessive risk? Have you seen stunt accidents that shocked you?

Yes, I have done a few risky performances, but the greatest accidents always seem to happen outside of my profession, working in the garden or riding a bicycle. I hardly ever abandoned the project because of its difficulty. Although I had a project in mind which was crossing from Europe to Asia, in the area of Istanbul, but I actually never pursued this it. The Pilsen walk, was actually more dangerous than I anticipated because it took place in the winter time and at night when it was humid out and the cable could have frozen up and it would have made it impossible for me to accomplish the walk. You must understand I’m actually not a performer that is looking to do stunts and to impress the audience in that way. I like the poetry and aesthetics of movement. But I also like happiness and making people happy. With humor, music and crazy acrobatics. I actually don’t like to see stunts that go wrong. I suffer watching people getting hurt. I’m especially irritated when people replay recordings of accidents because most of the time they would probably do it to monetize the issue. I think one shouldn’t provoke the good karma.

Let’s start from the beginning. Your father is considered to be a national treasure of Switzerland. When he died the Guardian wrote : “Switzerland’s favorite mime artist Clown Dimitri, a student of Marcel Marceau, made his name as a man of few words in a country with four official languages.” He wanted to be a clown from the age of 7 and you wanted to be an acrobat from the age of 9. Did he deter you from pursuing this demanding profession or did he encourage you? How was life in such a creative family?

My parents never impose any direction in my life. Of course, they were happy to know that I like the arts and that I like to train and try to become a circus performer and to play an instrument and to make things with my hands, craft-man things. My father was constantly rehearsing all the details of his performance or creating new things, building props for his show, creating artwork or writing funny things. We really had a lot of fun at home with my father because he always had an unusual and many times very funny approach to things. But don’t misunderstand, the fact that my father was a clown did not mean that at breakfast there was a clown sitting next to me every day. Clowns take life very seriously. But that’s because they are so interested in the world, in people in what’s going on and how to solve problems and ultimately how to make people smile. When we used to be sad, me and my four brothers and sisters, he always found a way to make us laugh and make us forget about being sad. But when I started my education at the state Circus school in Budapest, obviously my parents were very happy. They were certainly not the kind of parents that wished their children would become doctors or lawyers. All the contrary, they were supportive in my dream of becoming an artist, to become a wire walker in the circus.

A parenthesis as a continuation of the previous question. You are one of the most qualified people to tell me why many children are afraid of clowns (I was one of them). Have you discussed this matter with your father?

That’s a very good question. You might not believe this, but when I was a small kid, and my parents took us to the circus I actually was afraid of some of the clowns that I saw in those days. You know, the clowns with the red nose and the pink wigs and scenes where one clown would hit the other clown over the head with a oversized hammer, and they would laugh and cry and water would come out of their eyes… clowns that are not really clowns. They’re more like dressed up individuals in goofy costumes, but without any concept or fine sense of what it meant to be a clown. Some of the good clowns actually don’t have to do much. My father, for instance, was able to just stand on the stage and look at the audience, just look at them without any words and people would laugh. Of course, there is always the aspect of the unusual appearance of a clown, especially for small children. I remember when I was a small boy. There was a brief period where it felt strange to see my father with his make up on, especially because he was my father, and something was different about him that way, and that made his appearance spooky for me. My father tried to avoid using easy tools like extravagant elements or force. He always went to the poetic way and try to involve the small people in a way so they would feel comfortable and would laugh together with the big people.

You are not just walking a tightrope, but you are also a “One man Circus » with many years of studies. You started studying at the age of 14 at the State Academy of Circus Arts in Budapest. You then pursued intensive dance studies at the legendary Julliard School in New York which is synonymous with competitive excellence, total dedication, and rigorous training. What was the process to accept you, as they ask for hard-to-find talents with the prospect of global exposure. Did you ever feel like giving up because of the grueling tests the training required?

I’m an optimist, and I think that helped me to stay motivated and focused on the goal and purpose of my journey. This made me accept, to go through certain hardships. Looking back to the days when I was training really hard, I tell myself if I would have known how hard it is and how many years I would have to invest in learning all the skills I think I would have never embarked in this adventure. But I didn’t know how hard it was and how long it would take and that is good. The reason for accepting me at the Circus school was probably a mixture of my father being an established artist, and on the other side with Hungary still being a communist country, but being allowed by the Russian government to invite students from the west, and being able to generate foreign valuta for the ministry of culture. So, it was very easy to get in. On the other hand I got in at Juilliard school in New York with the help of a choreographer friend who was teaching at Juilliard and, not that she was able to influence the jury at the exam, but she helped me with a quiet original dance piece that combined dance with juggling. This intrigued the director of the school, Martha Hill, and so I got accepted. But I didn’t have much dance training at all, not like all the other admitted students that already had years of dance training.

Until you ended up creating your own show in 2001, you worked in two different types of circuses, equally famous worldwide. In the spectacular spectacle of the three rings, Cirque du Soleil and in the one ring, Big Apple Circus, whose intimacy, and immediacy is said to be unsurpassed as “you can smell the sawdust and see the sweat glistening on the faces of the acrobats”. Describe to us what was your part in each performance and what is the difference for an artist that participates in so many different types of circuses? Which of the two did you put more effort into?

That’s true I had experiences in different types of circuses. The first one, the one that still most of the people refer to is actually the ancient traditional, ethnic circus or folkloristic type of circus which was really created for amusement, public entertainment, and it consist mainly of physical feats and less in conceptual moments. That’s why in the traditional circus you’ll find a juggler for instance who would be doing his seven-minute act and basically perform this act of his entire career. He travels from one Circus to the other, from one contract to the other throughout the world, that could be a three months engagement in Las Vegas and then a nine months engagement in a touring Circus then he would go to a hotel in Singapore or do a tradeshow for some cookie company or auto manufacturer. Then there is the kind of new circuses like Cirque du Soleil, and I must say the Cirque du Soleil is really unique as they conceive entire shows based on a theme and they kind of create the show around this theme package it extremely well with all the details from music to costumes to the make-up and each individual performer does not necessarily have to bring the emotional aspect of performing like in a traditional circus where you really stand sometimes all alone in the center of the ring and your charisma really counts. At Soleil you could very well be a highly trained gymnast that Cirque du Soleil would hire and would make customs for you, put makeup on you and have you do your technical skills that you are specialized in and it would fit perfectly in their show. But in a way each individual can also be replaced so there is less of an individuality as there is in traditional circus. But then there is even another kind circus, called contemporary circus which certainly Soleil has aspects of, but the contemporary circus is really based on a creative innovative, sometimes experimental approach where the depth of the meaning has maybe a more important role. Where the technical skills sometimes are not as important as the concept of the performance. The contemporary circus has a much wider horizon in the sense that in contemporary circus you’ll see the combination of incredible circus technique with body movement like in contemporary dance combined with sounds, which could be performed by musicians live or sounds that are pre-recorded, and that whole combination of different types of performing arts methods will make up the contemporary Circus of today. When I started out, I started out in traditional Circus with Circus Kinney in Switzerland or in the big Apple circus in New York. There I would train every year an another act, sometimes I’ll be doing somersaults on a tightrope the next year, I would be doing a horseback acrobatic act, or aerial performance, this all with the same circus. I spent over 10 years at the Big Apple circus in New York. My engagement with Soleil came unexpectedly when they needed a main protagonist in the show, and so I jumped in and was part of an entire concept in the part of the “king of fools”. In that show, I was dancing, jumping and even doing little acts here and there, I needed to animate through the show. And then with the years I heard more and more about contemporary Circus, which mainly emerged from France, where no more circus families do circus but young artists that had no circus background created new ideas, using circus skills and brought in an entirely new era of circus in the late 80s and 90s. Nowadays, contemporary Circus is recognized by governmental funding in most European countries and around the world which in the 80s was nonexistent. This new funding started in France with the cultural minister at the time who realized the importance of contemporary Circus, to the point of making circus schools part of universities level enabling to receive a bachelor or even a master’s degree in Circus performing arts. France had the first such school, followed by Canada and then many other countries. Whereas the traditional circus remained unfunded. More like show business equal to what can be seen on Broadway, where it is much business oriented. Sometimes I got involved in high wire walking. That’s an entirely different approach. Because that kind of performance is in a completely different setting, mostly open air at a much largest scale in the sense that there could be thousands of spectators watching your performance high above the ground and from an entrepreneurial standpoint, it is also something that most of the time would be funded by a city or a sponsor that has an interest in producing such an event, and is less financed by ticket sales like it is common in the above mentioned types of performances.

Let’s finish with America. There you were also active in other fields of entertainment such as Hollywood and Broadway. Did you do it because you were experimenting, having not decided whether you would dedicate your career to the circus or did you do it for the experience? Have you worked with celebrities from the film or theater industry? You saw Robert DeNiro and Audrey Hepburn being regulars at the New York circus. What do you think it was that made them be so interested in this spectacle?

Coming from a family with a very wide background in the arts and performing arts, my grandparents were basically all artists they were painters, sculptures, architects, and my parents were performing artists my father was a clown, I met my father’s friends performing artists and so it was obvious for me that in New York my hunger for learning about all kinds of aspects of the performing arts world did not stop at the doorsteps of the circus, all the contrary, I wanted to go inside theater and the Opera House and the film industry and even commercial jobs for advertisement were intriguing and I was picking up all the opportunities that I had at the time. My first encounter with the film industry at the beginning of my travel to the United States when I was 18 and I had just started performing with the big Apple circus when Hollywood asked the big Apple Circus to be part in a movie which was called Annie, sort of a musical remake of an already existing movie with suspense, humor and music, and as I said, Circus. And so I spent quite an extensive time on the sets of that movie and got to know a so-called celebrities at that time like Albert Finney, Ann Reinking, or John Houston, and that was kind of motivating. Then I had gotten jobs with Franco Zeffirelli at the New York opera at Lincoln Center and I was working with Jean-Pierre Ponelle at the Metropolitan Opera house and then I performed with the Apple Circus where every other someone known would be sitting in the audience. That could one night be Dustin Hofmann or Robert De Niro and the next evening Donald Sutherland, Audrey Hepburn, Faye Dunaway. And, believe it or not I even shook hands with Donald Trump at that time as he showed up one evening with a donation check to the big Apple Circus for $15,000 (this was in the 80s ). Little did I think that someday he would become what he is today. I had many nice encounters with people that I highly admired, sort of in an absurd situation were one evening I might have seen someone on the big screen in the movie theaters and the next day she would be sitting in the first row, watching me do my somersaults, making it almost look like she came only to see me doing my somersaults on the tightrope and come greet us after the show. That was unique.

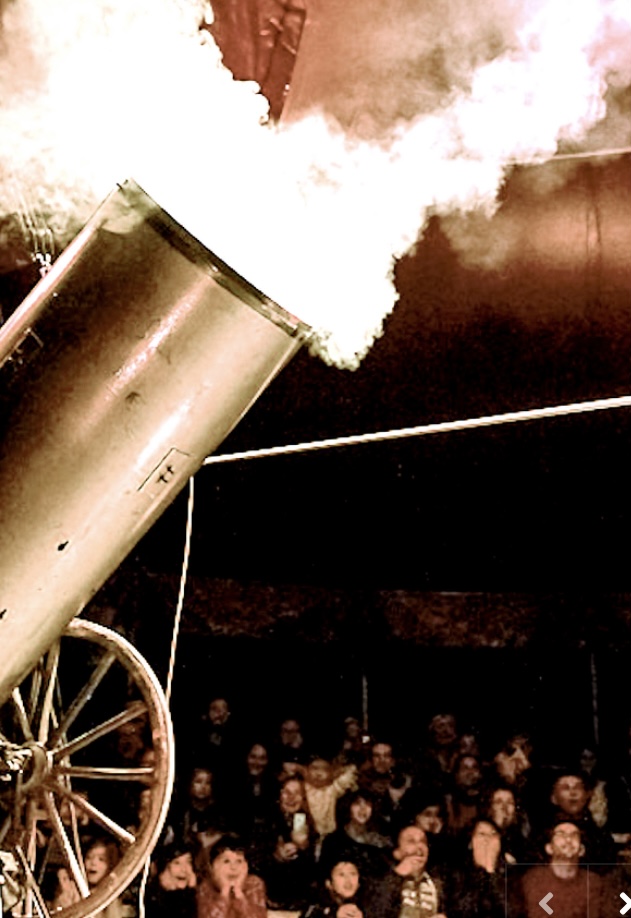

One man Circus (L’homme cirque) is an exciting Nouveau Cirque show that you created in collaboration with your father! A solo performance where the most daring and even extremely dangerous acrobatics alternate – like an intelligent orchestration – with comical, self-sarcastic numbers creating all in all, an unforgettably poetic performance. The pursuits of such a play go beyond impressing through display of skill. It is an art form that appeals to emotion and has much in common with theatre. What did you want the audience to feel when you conceptualized the performances?

With L’homme cirque, I wanted to let the audience in to my very own intimate work as a circus performer. At first, not really consciously so much as just wanting to show them my skills, in a very humble and maybe a little naïve way. Because my father had supported me on the idea that I had something to offer just by putting all my skills together and presenting them to the audience. And it was important for me at the same time to present myself in an intimate setting. Which quickly brought me to the most obvious idea of a little circus. So this interesting structure became an important part. I had no real established concept in my head in the sense of emotions and what I ultimately wanted people to gather from what I was offering them. But over the first few years of the project, I realized that the honesty, in the way I was presenting it, was the right path. This combination of the modest man trying to be funny without being a clown, risking his neck to amaze the people and trying the impossible, and on the other side the unpretentiousness, this felt right. It give the performance it’s signature. As a performer, I am very anti-gimmick. I don’t feel like cheating on people or have the audience laugh on someone’s account, stripping that person with a show-participation just to capitalize on laughter, without any artistic sense behind it. So my show evolved in basically not doing very much at all except for showing my skills that I had trained for decades, and which I was now able to use as instruments. In the Performance I’m going through a common moment, together with the audience and have them get to know me. I think the world needs moments for people to feel important to feel welcomed to be able to smile and not to feel threatened and that is my goal to create this ground for a human world that I am living, and people are living through me. I hope this makes sense.

How do you plan the acts of the show? What are the stages? Can you describe them to us step by step? What is the combination of arts required in your performances. How many hours do you train?

That’s a difficult question, because me too I’m still searching for the perfect procedure for the perfect process of creation. My inexperienced way I think was a unique approach because I just started by adding all my skills together and showed them to the audience. So, no clear, structured way of creation. But that was a lucky punch. In a new Project I would probably starting by doing nothing at all and developing this doing nothing-moment into actions. So that you would have a kind of a neutral status from which things will evolve. Because doing nothing could sometimes be more powerful than doing very much. Of course, that sounds really simple, later comes all the aspects and difficulties of sustaining the momentum of the piece, of sustaining the poetic aspect, of sustaining the emotion, and making it valuable. The process phenomenon is best described by the master of THEATRE, Peter Brook, who claims that unfortunately much of what exists in the performing arts is dead. He talks about the dead theater or the dead performance. And that basically comes from simply not having succeeded in creating something authentic, something that is emotional. And unfortunately, there is no user manual in how to proceed. There are many ways you can build a performance. There are many approaches. Ultimately, it’s the authenticity that makes something meaningful. That doesn’t mean a simple somersault could not be all that, but it would have to be executed in a specific way with a specific impulse or reason. My training consists in many aspects of life. Not all training is physical. A lot is done in my mind. But the hardest training still is on the tightrope, training my body, and my motor nervous system.

What is a technical part of this performance that is not easily perceived by the audience?

Who are the factors that as viewers we don’t see but their contribution is crucial?

I understand your question, my show is pretty straightforward and whatever you see is what it is so it might not be a good example for containing those aspects that you are talking about. There is certain levels of difficulty and danger, for instance, the high wire is a skill that relies on aspects from the outside, such as wind or weather condition that could make it difficult. For example, a difficult feats is a forward somersault on a 12 mm cable. But this is obvious that it is difficult and so I think in my show the different levels of danger and difficulty are easily visible. The most difficult invisible aspect is to create the magic of a performance. You could have all the tools in the world, but if you cannot bring your performance to live then there is no sole.

Why do we think that circus people are gloomy even though they make us laugh and be happy? You have said that ” If there is nothing to laugh about anymore, then we are in a very bad place”.

This indicates a very optimistic personality. But why is there a widespread perception of the melancholy of circus people? What is true? What kind of person would you say you are?

I think it’s two kinds of states that performing artists are in. One is the performing state where they use their skill to make emotion come alive. But that same person is also a person like everyone else with his own character and daily problems and baggage. And so, it could very well be that a clown that is very funny could be somewhat sad or frustrated in life outside of performing. Or this performer could be a very positive person in private life, like my father was. I look at myself as a positive person, I tend to always find solutions and be optimistic in all I do. Which helps if you want to be a high wire walker and you’re crossing a cable, 60 m above the ground. Because when you come to the middle, you don’t wanna be in a state of depression and have dark thoughts. Ha ha ha. Sometimes performers might be seen backstage in a moment where they are not performing, maybe talking on the mobile phone or eating a sandwich, a total demystification of the personage.

To be a performer is not easy at times. You’re always on the road or away from family or places you miss. But the same could be said about anybody with a regular job, to feel stuck in one place with the longing of something in fare places.

Important is to dream. And then start building the plan to realize that dream. That’s how I do it.

You are artistic director at the Winterfest festival in Saltzburg, and you manage the Fondazione Dimitri founded by your parents, a university-level school with Bachelor and Master programs. You are a personified Swiss knife! How do you manage all this? What are your responsibilities in each of them?

You are right, I am multitasking a little bit too much. I actually gave up my position as artistic director at the Winterfest in Salzburg, where I was responsible for recruiting the best circus companies in the world I could possibly find and creating, shaping the festival of contemporary Circus every year. Now I have more room to accomplish other tasks better.

My work at the Fondazione Dimitri consists in fundraising and animating the unique cultural center that my parents created in the 70s. This is one of my big responsibilities right now, as it is very difficult for a cultural center to survive. Fortunately, the brand Dimitri is unique and appreciated by many people, and therefore, as president of the foundation it makes my work a bit easier. It’s a great opportunity to do this work in keeping the spirit and the mission of bringing emotional values to the people alive. My parents donated their real estate portfolio to the foundation. And this is the basis and the pillar for the organization’s existence today. And I’m responsible in making sure it stays that way.

My parents also founded the Dimitri School (Accademia Dimitri), which has about 50 students every year. They can graduate with a bachelor’s or a master’s degree. Together with the theater the museum, the theater restaurant, the Accademia, the little cultural center has gained its importance in the southern part of Switzerland.

Which of the movies that have been made about the circus do you love, and which do you consider the most realistic about the life of the circus performers?

– La Stada (Fellini)

– I clown (Fellini)

– The Circus (Charlie Chaplin)

I have many others, but they don’t come to mind right now

You have said that interest in the circus has increased in recent years. What has changed and what kind of circus has the greatest acceptance and at what ages?

Besides the big industry of Cirque du Soleil, I think the new circus, the contemporary circus, which goes beyond Cirque du Soleil, is for me the circus of the future, the circus for families for intellectuals for people like you and me, because it’s the most innovative and the most creative and the most human and honest of circuses. At the same time, I must say that there is no other circus like the traditional one, with the nostalgia, the sawdust, the clowns trapeze artists and it will always live on.

How extreme of a person are you outside of work and what relaxes you?

I’m not extreme at all. But maybe because of my lifelong challenges in doing what I’m doing I might have more tendency of embarking in unthinkable, new projects then a person that doesn’t have such a background. The important thing is to know your limits. I used to work with two young South Africans, that grew up in the ghetto, under difficult circumstances, and they turned out to be world famous with their absolutely incredible and dangerous aerial performance. So maybe their situation and perspective in life got them to try unthinkable things. Maybe these same two young acrobats, if they would have grown up in a well-established neighborhood with no existential challenges, they might become bankers or postmans or insurance agents without the drive and motivation. I’m not out of the common in real life. My father taught me to look at things in my own way, and not in the way the media or other groups of people tell me to. To think on my own and create my very own life in my very own environment, products, performances.

David Dimitri is an artist that embraces the beauty of life. Eloquent, willing to go into the details and with amazing descriptions, he meticulously shared his experience with me. His explanation on the concept of fear before a performance and his ability to transform his answer into a universal theme which is relatable to everyone demonstrate his emotional intelligence. His insights on the circus and the broader cycle of entertainment are valuable, as he brought down many stereotypes that had consumed when I first learned about circuses in elementary school. I think the takeaway lesson from our communication is his unique approach to life. Life is risky, unpredictable but worthy of exploring its every aspect. That is what he has proven, from the way he balances himself on the tightrope to the way he balanced his answers to my questions.