Dionisis Simopoulos

Fly me to the moon

MAY 31, 2022

“Do not go gentle into that good night,

Old age should burn and rave at close of day;

Rage, rage against the dying of the light.

Good men, the last wave by, crying how bright

Their frail deeds might have danced in a green bay,

Rage, rage against the dying of the light.”

Mr Simopoulos, I will begin by making an introduction. I want to tell you that within 3 weeks, I did everything possible to come up with questions through the knowledge I have on the matter. I have practiced a lot to not sound like a robot. I promise to do my best.

No problem.

I think I will be fine.

Don’t worry. Even experienced journalists struggle in such interviews.

Okay let’s begin. My first question is about black holes which are also called donuts because of their shape. Oscar Wild says that an optimist sees a donut, but a pessimist sees the hole. You as an astrophysicist, how do you perceive this space donut?

(laughter) I would say that I view black holes, like other natural phenomena, as something that, although difficult for the human mind to comprehend, can nonetheless be easily processed if we possess the necessary knowledge. For example, Albert Einstein, as early as the beginning of the 20th century, provided us with the opportunity, through the General Theory of Relativity, to predict the existence of such objects. These objects have the ability to absorb even light, meaning that no information can escape from them. Therefore, for the past 100 years, despite having both theoretical and practical answers to the question of what we call black holes, the photographs presented three years ago from the M87 galaxy, and just days ago from our own galaxy, prove the truth even more convincingly.

I intended to ask you this exact question. I want to understand how the black hole is connected to theory of Relativity. I know that the answer to this was given by another charismatic scientist, Karl Schwarzschild.

The mathematical solution of the equations regarding the Theory of Relativity is very difficult, and I can tell you that even Einstein did not bother to solve them himself. He left that task to his colleagues. As you correctly mentioned, Karl Schwarzschild and, of course, those who followed later. In the case of Schwarzschild, he solved the equations for a very simple black hole. Later, more complex solutions were developed for rotating black holes. This way, we gradually gained the knowledge that led us to understand why certain regions of the sky contain these “strange beasts” of nature. For example, one of the earliest hints of the existence of a black hole was a source of X-ray emissions in the Cygnus constellation, named Cygnus X-1. This source was later confirmed by other methods to indeed be a black hole. However, since it had not been photographed, we did not have all the information, and we had to wait for the imaging of these massive black holes at the centers of our galaxy and M87.

On this, I would like to ask about Hawking and his theory about the paradox of “information return”? What is this exactly and how does it relate to the discovery of the last information we have on space?

For information to escape the gravitational pull of a black hole, this force must be greater than the speed of light. Otherwise, even light, despite traveling at a speed of 300,000 km per second, cannot escape, just like any other information. However, Hawking told us that even in this case, once in a long while—when I say once in a long while, I mean perhaps thousands or millions of years—a tiny bit of information can escape from a black hole. This is why black holes slowly evaporate and disappear. In fact, even the smallest black holes, which we believe were formed during the birth of the universe, 13.8 billion years ago (after the Big Bang), because they were incredibly small and microscopic, have evaporated, and such black holes likely no longer exist in the observable universe.

Recently, we managed to successfully take pictures of Sagittarius A. Why is this important for us, and how will it impact our daily lives?

First and foremost, the development of technology. The collaboration of 350 different researchers from 20 different countries and more than 60 laboratories and universities around the world. All of this represents significant progress in advancing science. You know, science has gradually evolved to a point where, due to its complexity in recent decades, it’s becoming very difficult for one person to carry it forward alone. Still though there are brilliant individuals who can make strides on their own.

A recent example is Psaltis, who has invested a lot on this matter and even got close to receive a Nobel Prize.

Yes indeed, Psaltis in collaboration with 350 researchers from all over the world managed to build a huge radio-telescope. Funny thing is that it isn’t one big telescope.

Apologies for interrupting you, but I think I know what you are talking about. I have seen in a documentary, that this telescope is made up of 8 different telescopes that are in distant locations around the earth. All 8 take pictures of different parts of the black hole to build one big visual representation.

Yes, essentially, because these individual radio telescopes operate interferometrically, they combine and give an image similar to a great telescope. As you can understand, this development is not entirely new, but it has now progressed very quickly. Initially, we had the array in Socorro, New Mexico—I can’t recall the exact number right now, but it must have been 27 different antennas. Various radio telescopes worked together interferometrically.

What does function interferometrically mean?

That the telescopes combine and function as one unit.

Okay, I see. Because we cant have telescopes at the size of the earth we build several codependent units to acquire visual representations of the desired magnitude.

Exactly!

Beautiful and despite the discoveries that have been made, why doesn’t science dominate as a way of thinking? I recently read about a course with the incredible title, ‘Calling Bullshit.’ The academics, West and Bergstrom, are pushing back against theories that claim dinosaurs never existed, the earth is flat, etc. These ideas not only sound ridiculous but also have a large audience. Even though we have reached a point where we make such discoveries, why is this happening?

Because people are stupid, what can we do? (laughs) You show them evidence, and they insist: ‘We didn’t go to the moon!’ These are conspiracy theories.

Yes, but how can the scientific method be integrated into our education?

But every day, education is based on a scientific method. It’s another thing if teachers, professors, or even students don’t realize it. The foundation of any progressive education—because there are various types of education—is the scientific method. Whether we’re talking about the sciences, ancient Greek, or history, everything is based on what is called the scientific method.

Perhaps an example of what I want to say is the fact that we don’t learn astronomy in our schools. We don’t gain knowledge of this subject in our basic education. If an astronomy course were taught to us only through films, it would be a really great way to gain a deeper understanding of the phenomena around us.

Look, you’re asking if a course in astronomy, for example, could be really good with the help of videos. Well, it’s possible. It probably happened when astronomy was taught in schools. There were also some enlightened teachers who formed small groups where students created and presented the day’s lesson with the help of the teachers. There are many different effective ways to make such a lesson visual. Don’t forget that the images sent to us, especially in recent years, from various space telescopes, even from ground-based telescopes, are truly works of art. This could really impress students and encourage them to learn about the environment known as the universe. Unfortunately, astronomy has been removed as a subject, and children no longer have the opportunity to gain basic general knowledge about the universe—even just once in 12 years of primary education. That’s essentially about 30 academic hours. Within those 30 hours, a good teacher could convey a lot of wonderful information about the universe.

In the flexible tome zone at middle school, once a week we deal with all sorts of trivial topics, while we could actually focus on something much more useful.

I think it’s forbidden to include astronomy topics in the flexible time zone, but I’m not sure.

Why has this been forbidden?

That’s a good question for those who make the decisions.

In the States, there’s the Smithsonian Institution, whose main goal is to increase and transfer knowledge through the methods we are discussing.

Just a moment, pay attention. The States have certain institutions that are advanced, including the Smithsonian, which deals not only with astronomy but with everything related to science, even history. This is a process that has been underway for decades; it’s not something new. Unfortunately, here in Greece, we don’t have such opportunities.

So, the Eugenides Foundation, for example, comes along and says, ‘Okay, I’m not going to teach students or the general public astronomy, but I will allocate my own funds—money from the Foundation—to help visitors get a general understanding of the universe.’ This is happening in Greece as well, on a limited scale. And it’s not just the Eugenides Foundation with the Planetarium, but also the Goulandris Museum.

Hellenic Cosmos as well.

I don’t think the Hellenic Cosmos fits within the framework defined by the operation of the Smithsonian, which is more in line with the Goulandris Museum, the Eugenides Foundation, and similar institutions.

You got me because that was my next question about the Eugenides Planetarium. With your own ‘my way,’ you managed to turn the planetarium into a laboratory for understanding the universe. How did you develop this scientific mindset?

Look, I was a storyteller from the very beginning. I enjoyed telling stories about the universe. Whether I was with the scouts talking about the constellations we saw on trips and while camping, or later more intensively. So, from the start, I had decided that I didn’t have the temperament of a researcher, because whatever I contributed to the research field was limited.

For example, my professor was preparing me for research in the evolutionary path of stars, specifically in Stellar Evolution. At that time, in the 1960s, I wasn’t very interested in that. Back then, you had to go to high mountains, use telescopes, and make observations. We didn’t have the same conveniences as now; you sit at a desk, drink your coffee, and get your information from Chile while you’re in Germany.

So there was an opening for me on three different levels: in theory, like Dimitris Nanopoulos; in practice, like Stamatis Krimizis; or in education, in the dissemination of science, as we used to say. I was more interested in the dissemination of science because my professor was truly a Renaissance man and guided me in that direction. He encouraged me to create, or rather he himself created for me, a study direction that led to a career in popularizing science. This direction, combined with the courses in communication and organizational development that I had already taken in my first degree in communication, led me to focus on planetarium management and the dissemination of astrophysics.

In general, I had a curriculum of three different specialties. The good thing about American education is that you have the freedom to take a variety of courses until you decide what you want to pursue. Once you finish those courses, you receive the corresponding degree.

Essentially, you are given the flexibility to change your mind because when you start university at 18, it’s not always easy to know what you want to do for the rest of your life. You don’t know anything. So, what happened in my case was that thanks to the American higher education system, I was able to take elective courses that interested me and were easy for me, such as physics, chemistry, and mathematics, but also, thanks to my professor’s enlightened perception, I was able to take other courses that would lead me to the work I did for so many years.

In your book, you write that you had the astrophysicist Carl Sagan as a sort of mentor from the moment you met him.

Just a moment, mentor in the sense that I was trying to follow the same approach that he had.

Because Sagan was somewhat like the Yoda of astrophysicists.

Exactly. Sagan did conduct research, but primarily he focused on what I suppose interested him more: the dissemination of science in an easy and understandable way. Hence, he created that wonderful series Cosmos, which has never been surpassed since. Even the efforts made by the director of the New York Planetarium cannot compare.

Neil Tyson?

Yes. Yes. It cannot compare to the truly enlightened perspective that Carl Sagan had. He was one of a kind.

I read an excerpt from Pale Blue Dot, the famous poem he wrote. The way he articulates and describes the beauty of the universe is truly unmatched.

Yes, yes, but he also had the support of the producers because of who he was. If I remember correctly, he spent $800,000 on each hour-long episode of Cosmos. And we’re talking about the 1970s. That was a huge amount, but they trusted him, and rightly so. This series was presented in 60 different countries, and the producers ultimately made a lot of money.

Cosmos featured the music of Vangelis Papathanassiou. Our great Greek contributed creatively to this series as well.

Vangelis Papathanassiou is also a Renaissance man. He passed away a few days ago.

Unfortunately.

Really, we miss him very much. He was a very humble man, an amazing cook, a fantastic painter, and a wonderful musician. He advanced music even though he was self-taught and didn’t know how to read music. Nevertheless, he progressed music and used instruments in a completely different way than they had been used until then. He was truly something, that man!

I’m glad to hear that he was not only a great musician but also a great person. Something I read and don’t remember well is about how he ‘connects’ his music with space.

Look, like any great genius, Vangelis had his own perspectives. For example, he once told me that the music you hear isn’t music I created, but rather existing music that is out there in the universe, and that this universe uses me as a medium to bring it to Earth and to people.

Truly surprising! Now let’s return to you, Mr. Simopoulos. Let’s talk about the planetarium. What exactly does a planetarium director do? It’s certainly not just an administrative position. You are an astrophysicist, and your articles on the Eugenides Foundation’s website are in a section with the mysterious title ‘Astropyle.’ This somewhat hints at the complexity that lies behind it.

A planetarium director is a special occupation. Each director is different from another. In other words, there’s no specific type that one can follow. In my case, I was a bit obsessed; I was a bit of a show-off. I loved what I did very much. I turned my job into a hobby; I made my work fun.

What could be more important than that! Confucius!

I wrote the scripts, created the musical score, and managed an organization, but as I said, thanks to the help I received from my professor, I had the necessary tools. It wasn’t just about communication. It wasn’t just about managing organizations. It was also about astrophysics. All of this combined into a whole that cannot be said to be the same for any planetarium director. In my time, especially in Greece in the 1970s, I felt like a fly in the milk. There were many famous colleagues who looked at me askance. They believed I was vulgarizing science. Today, of course, many astrophysicists accompany their activities with such endeavors related to the development and dissemination of science. Each person naturally has their own personality.

Well, that was actually my next question. You came to Greece in ’72 and wanted to achieve the dissemination of science to the public in a simple way, and as a result, you became the managing director of the star system in the literal sense. But what was the cost of this for you? Just before, you mentioned that you were accused of vulgarizing science.

No, no, Panagiotis, don’t get things mixed up. Neither I nor my colleagues or collaborators ever tried to become part of what we call the star system. It just happened that what we said and what we tried to convey resonated with people. It was accepted by the general public because the public and the students were thirsty for knowledge. Let me give you an example to help you understand some things. Something significant was happening in astronomy: the discovery of a supernova explosion. We’re talking about the 1970s. Journalists were getting this information from various news agencies, but they were only provided with simple details. Greek journalists needed more information, so they would call where? The Planetarium! That’s why journalists, to write beyond the information given by the agencies, would call Simopoulos. They knew me, so they would reach out and say, ‘Hey, this and that…’. In order to answer their questions, I needed to have more information. However, at that time, we didn’t have the internet or anything. So, I had to wait one or two months for information from various specialized magazines to learn what the heck we had discovered. But the journalist couldn’t wait two months for me to tell them what we had discovered. What I did was provide background information. For example, we learned about black holes. I didn’t give information about the specific black hole X1 Cygnus, but I provided information on what a black hole means and what a supernova means. I gave background information that supplemented the journalist’s news.

That is very clear. I expressed it as a metaphor. I meant that as the managing director of the planetarium, your ‘star system’ consisted of the real stars. In no way did I mean it in the conventional sense.

Ah, okay, Panagiotis, now I understand. Also, everything that happened over these 40-50 years—almost 50—was not done by one person, just me, but I had particularly good collaborators. So when one of my collaborators helped me in this dissemination of science, in popularization, they were a participant in this effort, and as a participant, you understand that I was particularly grateful for their presence. I was 29 when I started, but I grew older like everyone else, and of course, I always promoted my younger collaborators.

Do you believe that all this work had a toll on you?

It had a cost, but it was a family cost. I had the opportunity to go to the office later than usual, around 11 in the morning, but I left at 10 in the evening. Unfortunately, this had an impact on my children and my family. They didn’t see me often during the week. The kids had to be in bed by 9 in the evening when the main news started. There weren’t many channels back then; we only had two. When they saw the clock strike 9, they knew it was time to be in bed. So one time, when I returned home around 8, I learned from my wife that our son asked her, ‘Is Daddy sick?’ Sick because I had come home early. So yes, the cost was significant.

Beyond family, which is the most important, I want to ask you about your experience in Greece. For example, in ’96 you received the highest honor from the International Planetarium Society, in 2006, the Academic Phoenix from the Ministry of Education of France, and here you were awarded only in ’12 and ’15. It’s really shameful. 19 years later.

No, no. Look, everyone has their own choices. Each organization has its own choices, so I can’t judge the choices of other organizations. But Panagiotis, don’t forget this: all these distinctions, all the awards, whether from Greece or abroad, all these degrees, money, anything—they don’t go with you; you can’t take them with you, so they don’t matter that much. Of course, you feel pleased (don’t get me wrong) when your work is recognized by colleagues, by people, and by organizations, but you enjoy it for 3-4-5 days, maybe a week. After that, it’s back to square one. It’s not something you can control. But regarding your question, you should get my new book, which is quite autobiographical and will be released in the next 10 days.

What is the title;

The book is titled “Testimonies, the Salt of a Life.” If you’ve seen the film “Politiki Kouzina,” there’s a moment when the grandfather tells his grandson, “People love stories.” My life has been nothing but a life full of such stories. Some of these stories I’ve recorded while describing the evolution of the dissemination of science in Greece and abroad. It’s called “Testimonies” because it is based on phone conversations and memories I shared with M. Provatas during our confinement due to the pandemic, and later on. I must admit that, despite my initial hesitations, those discussions led me to recall events I had almost forgotten or deemed not very significant, while also bringing to mind people who had great value in my life, perhaps more than I realized at that moment. Testimonies of a life that, when viewed again through this new lens of the last three-plus years of health challenges I’m facing, shine somewhat differently within me—brighter, more radiant.

I want to ask you about the book you mentioned. Will there be a presentation for it?

To be honest, Panagiotis, I’ve started to lose many of my abilities due to my illness, so I don’t know if or when there will be a presentation. The fact is, it’s a very nice book, but it’s quite expensive because it’s massive. It’s around 24 euros.

But what it contains will be invaluable. You mentioned that awards aren’t what truly matter; it’s the experiences you carry with you. For you, what are those experiences? Your stories, as you mentioned earlier.

What accompanies me, Panagioti, and what should accompany any person, regardless of their status—be it simple, great, or small—is love. Love has no rival.

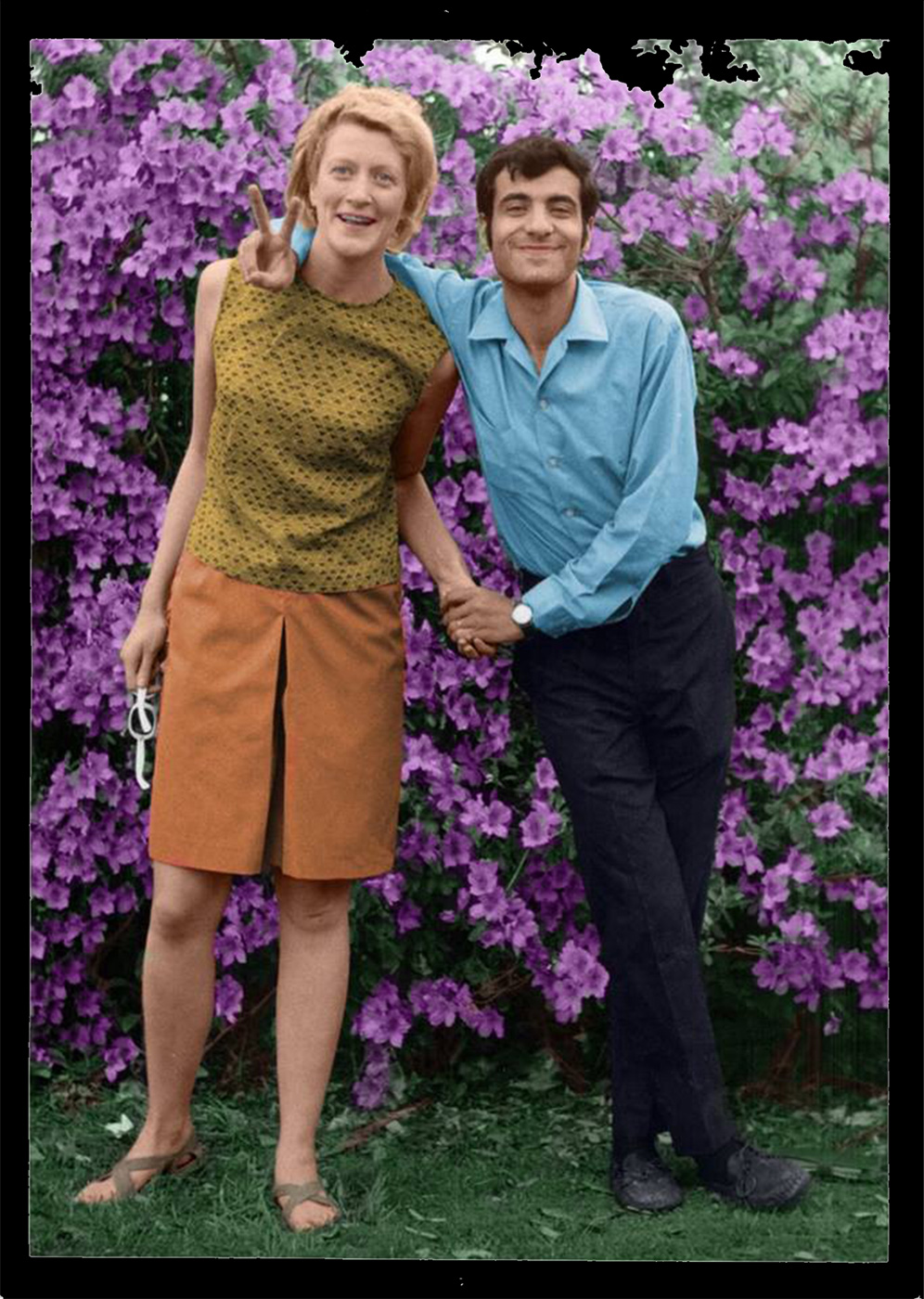

From what I gather from your books, family and friendship are your universe—they are everything, your stars, not just your planets. They accompany you everywhere. The youthful friendships you’ve maintained to this day, your gratitude for moments like those you describe spending Christmas in Lincoln with your wife’s parents, the photocopy you’ve kept of the paycheck you faxed to your mother to reassure her about your journey in America. And other moments, like choosing to be with astronaut Collins’s children while their father was on the Moon. Wonderful memories that reflect the love you speak of and feel.

Yes, that’s exactly it. It’s what essentially makes us human.

Regarding this, about memories: Hawking has said that our memories might one day turn out to be nothing more than illusions. Does this terrify you or spark your imagination?

Neither one nor the other. As we said, everyone can have their own views on anything. Can you prove it? Neither can Hawking prove what he said. You see? So, in that sense, even though Hawking is who he is, beyond astrophysics, he can’t claim to know everything about every subject. I respect his opinions, but I often see people on TV expressing their personal views on everything, from politics to music and entertainment. Well, you can’t know everything. So, forgive me, the late Hawking, but I don’t agree with him.

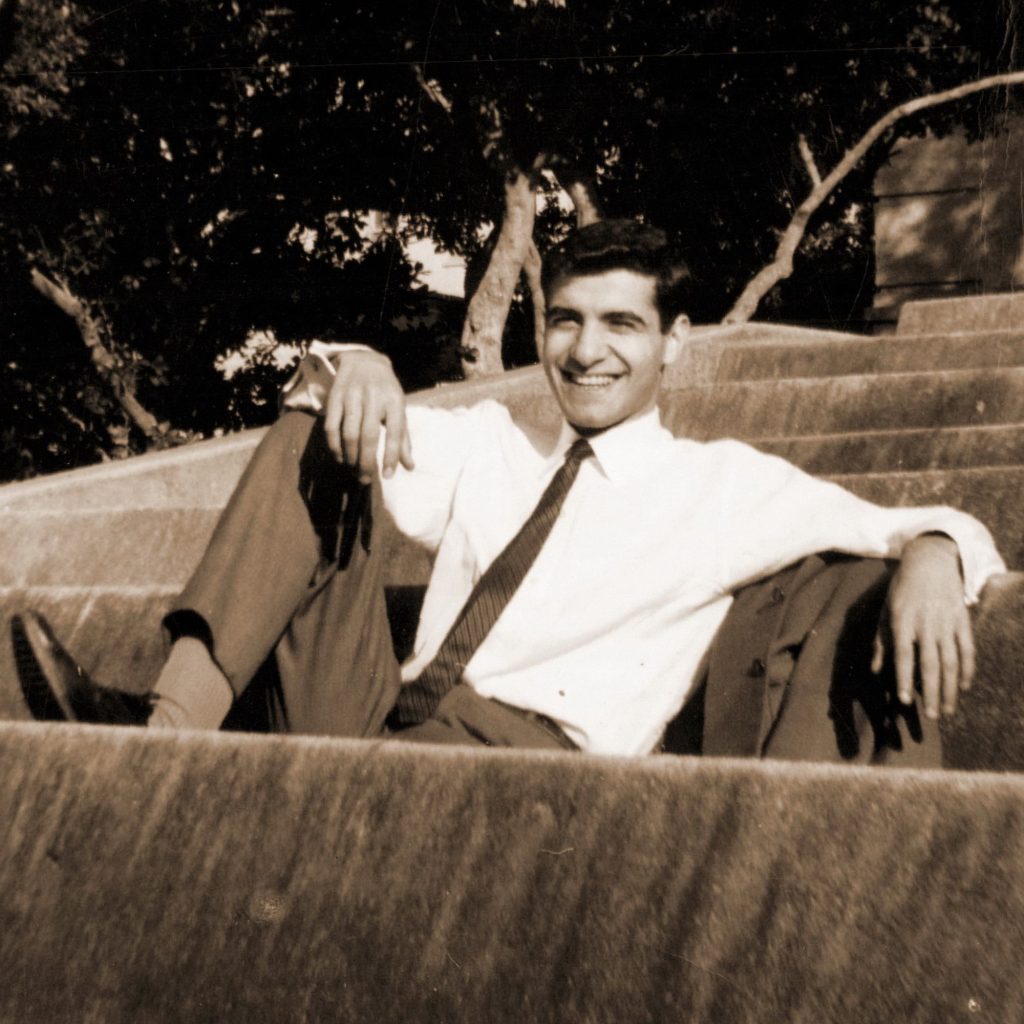

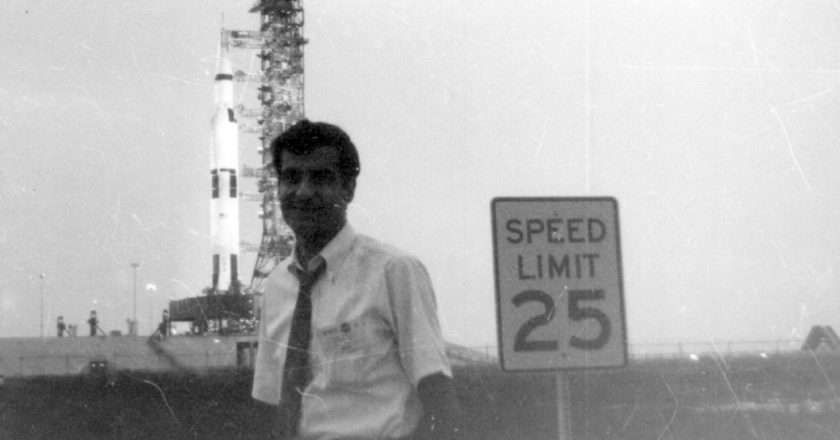

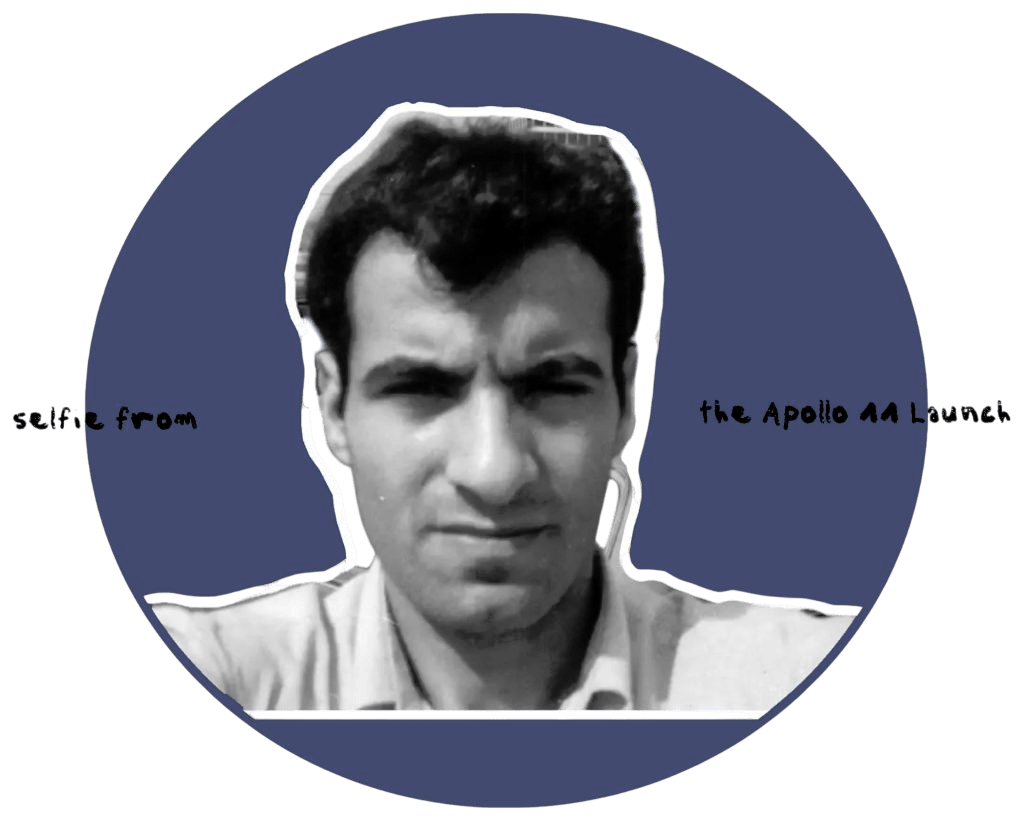

Let’s talk about something we’ve proven. Conspiracy theorists say we never went to the moon. But you, as a student of astrophysics at Louisiana State University and the only newspaper correspondent in Greece, were at the Johnson Space Center in Houston when the world heard Armstrong say, “The eagle has landed.” Tell us about the launch and what you experienced. What comes to mind? These aren’t general facts; they’re personal testimonies from someone who lived through it. What flashes back for you? What were you eating? What music were you listening to? Describe the atmosphere at the space center, the vibe.

Those were hard days, don’t you think differently. First of all I was at Cape Kennedy in Florida and in the afternoon when Apollo 11 was launched I took the plane and went to Houston because immediately after the launch, Houston had communication with the spaceship, the astronauts. Even at that time, even then, there were radio amateurs who could locate the source from which a small response was coming and had detected when Armstrong spoke saying that he was on the surface of the Moon. Who ? The radio amateurs! There are, of course, dozens of other examples that I can list that they can prove everyone who claims we didn’t step on the moon wrong.

In your book “From the Heights to the Moon” you write about the launch: “The sound that I heard was indescribable. It was literally pounding in my chest and I couldn’t tell if I was hearing or feeling it or both together”. Can you talk about this description?

This is terribly difficult to describe even today, fifty years later. This feeling I can’t explain it more. You have to experience it because really words are poor to describe this kind of situation. Those of us who were there didn’t have the opportunity to do anything else but react and work. You had to write all the time, send the responses to newspapers. I don’t remember how many total responses I had sent. There must have been at least some 40 articles in a period of about 10

days.

You didn’t even eat, it was just work.

Yes, not even food . You forgot to eat. Those situations were so shocking that you forgot. To let you understand. Indeed, the launch was very impressive, something I cannot describe in words. Indeed, the conversations I had with various experts of that time and with the families of the astronauts are unforgettable. For example, I had the opportunity to be with the three children of Michael Collins , the astronaut who stayed in orbit around the Moon. All this basically didn’t give you a chance to think about anything more at that moment, despite the questions you would ask. Michael Collins , had two girls and a boy, the youngest being a boy. When I asked, “what do you want dad to bring you from his trip” he replied: Ice cream powder. Something like a milkshake .

I have eaten it too. They brought it to me from the NASA booth in Houston. I pretended it was delicious with the idea that astronauts were eating it but it was like eating paper.

Behind all this, we are talking about 500,000 people who participated in the creation of this program, from various companies, from various industries that helped to get these first men to the moon.

In Houston you spoke with the holy – in quotation marks holy – for me monster, von Braun who had create the missiles of revenge for the Nazis.

A correction to avoid misunderstanding. This interview with Von Braun was not an interview like the one we do now, because he was very busy especially in the days before the launch. He couldn’t pay attention to a kid like me at the time. I was only 26 years old.

I sent him the questions and apparently, he didn’t answer them himself. It was not possible for him to sit and answer every journalist’s questions.

We are talking about thousands of journalists who wanted to talk to him. I assume that the answers were written based of course on the knowledge they had of Von Braun’s perception, by people of NASA public relations. So don’t think I was face to face with him.

I understand. How did the Americans feel about having to work with someone that had been a part of the Nazi war machine?

I can’t speak for all Americans, but I think from those I talked to at the time that they treated him the same way that the rest of the world treated the epic endeavor of space. It was a universal effort. We are not talking about something ordinary. After all, you said it too in the note that you sent me: imagine, imagine, imagine.

Because that’s the only thing we can do. Imagine what everyone was thinking at the time.

Let’s move on to another immense event that happened in houston. I will repeat the phrase : “ Houston , we have a problem ”. It is NASA’s greatest mission that failed successfully. Apollo 13.

In a public survey people were asked to rate how realistic the movie about this story is, and someone said that it’s a bad movie because such thing can happen in reality. Of course, they were unaware that this was a true event.

A true event that would have ended tragically, if it wasn’t for the greek engineer Kontaratos.

He essentially provided the solution to return the crew to Earth. Did you know him?

At that time, of course, I did not know Kontaratos well. We became very good friends later, in the 70s, when had returned to Greece.

But I would like to correct the following about “it was the biggest failure”. No 13 was not NASA’s big failure.

No, I said failed success.

Ah yes yes. Fail success. I didn’t understand, I’m sorry . Although Kontaratos managed this , he was a modest man. He was a lovable man, a truly renaissance man, and he was involved in many things in his life apart from his immense contribution to the Apollo program. He became president of the National Research Foundation in Greece. He was a professor at the University of Patras and later he was the one who literally created the Onassios Cardiac Surgery Center and the Henricos Dunan hospital. He was a man who also participated in the creation of biological material for cigarettes in special packages. Even at the end of his life, he was entrusted with the administration of Evangelismos hospital and thanks to him, the operating theaters were renewed. And how were they renewed? I think he came in an agreement with the National Bank, which sponsored this effort and because of his previous experience with Onassios and Henry Dunan, they asked him: “What do you want us to do for you in Evangelismos?” He told them the following: “I want to build 10 surgeries with the latest technology, but I don’t want you to give us the ability to manage the funds for this investment.

I want you to manage all this money from beginning to end.”

The man was something else. Unfortunately, before he even finished this, he became ill from his heart. In fact, he was being treated at the hospital he managed, in Evangelismos. Even there, someone stole his phone. The man in charge of the department, being there as a patient and he had his phone stollen. Terrible!

Unfortunately, this man who is the glory and honor of his homeland, Santorini, passed away.

A truly wonderful man. I didn’t know his service to us extended beyond NASA.

Mr. Simopoulos, let me ask you. Do you want to continue on Friday or can we finsih the interview today?

Look, Panagiotis, I’m not hiding from you that I’m tired . I think we’d better put it off until Friday. I will be more eager to answer questions then.

Perfect. On Friday I have an exam for a german diploma in the morning. I will call you in the afternoon if that’s okay.

Look at any time that suits you. I am available. In the meantime I’m sure the book will be out too, so I won’t have to worry about accounting **because you know sometimes accounting gives you more problems than writing a book.

Good luck with the accounting department. So we go for Friday. Thank you very much for your answers today. So far every answer is food for thought. It was a magical experience for me.

Be well , my Panagiotis.

Thank you very much, so we are happy to continue on

Friday! Good afternoon.

Take care!

*In a note I had sent to D.Simopoulos I had incorporated his own expression “imagine, imagine” . He liked to give emphasis to the power of imagination and how this becomes the driving force for the realization of our goals and dreams

“But every day, education is based on a scientific method. It’s another thing if teachers, professors, or even students don’t realise it.

Whether we’re talking about the sciences, ancient Greek, or history, everything is based on what is called the scientific method.”

In December 2023 , the Planetarian , the monthly magazine of the International Planetarium Society , dedicated ten pages to the work and personality of Dionisis Simopoulos . In50 years of publication, it had never given more than one page to honor a member who passed away. The extensive international tribute proves that his fame went beyond Greece. “It was not our initiative at all… On August 7, the day of his death, the Planetarian contacted us by itself, informing us that it would ask international figures in the field to speak about him” , said Manos Kitsonas , director of Eugenideon Foundation . He also points out that “I was particularly impressed by the paragraph added at the end of the text by the editorial director, who, being quite young, did not know Simopoulos . “.

The tribute includes a tender text from his beloved daughter Eleni.

“For the past four years, my father has been enjoying his friends, family and loved ones, writing a few books, eating his favorite seafood, going sushi crazy and watching cooking shows on TV. He used to put on music and sing as he wrote his books – some of them scholarly, others looking back at his whole life – but regardless of the subject, he wrote and sang.”

On Monday, August 8, 2022, one of his children, at his own request, changed the cover photo on Facebook with ” That’s all Folks ! and wrote:

“Our dad 2 days ago asked me to change this cover photo. He kept his humor until the end. “He left” with a smile on his face.