Νicolas Niarchos

Digging up for the truth

FEBRUARY 2, 2025

Nikolas Niarchos excavates truths that are deeply buried, revealing what we cannot fathom or confirming what we have long suspected.

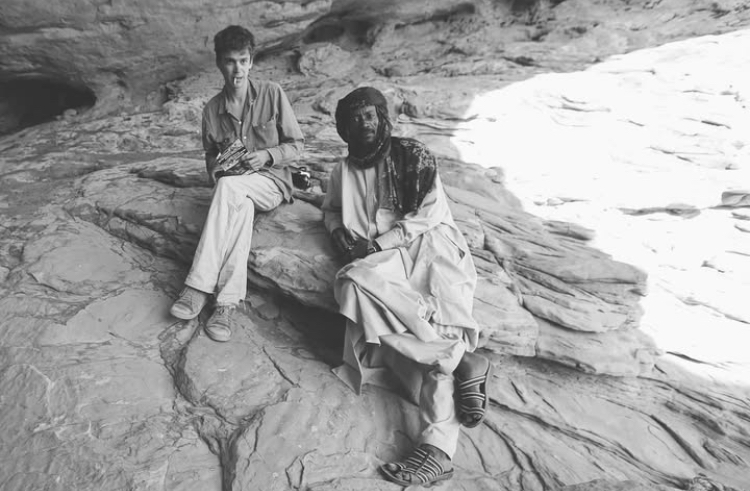

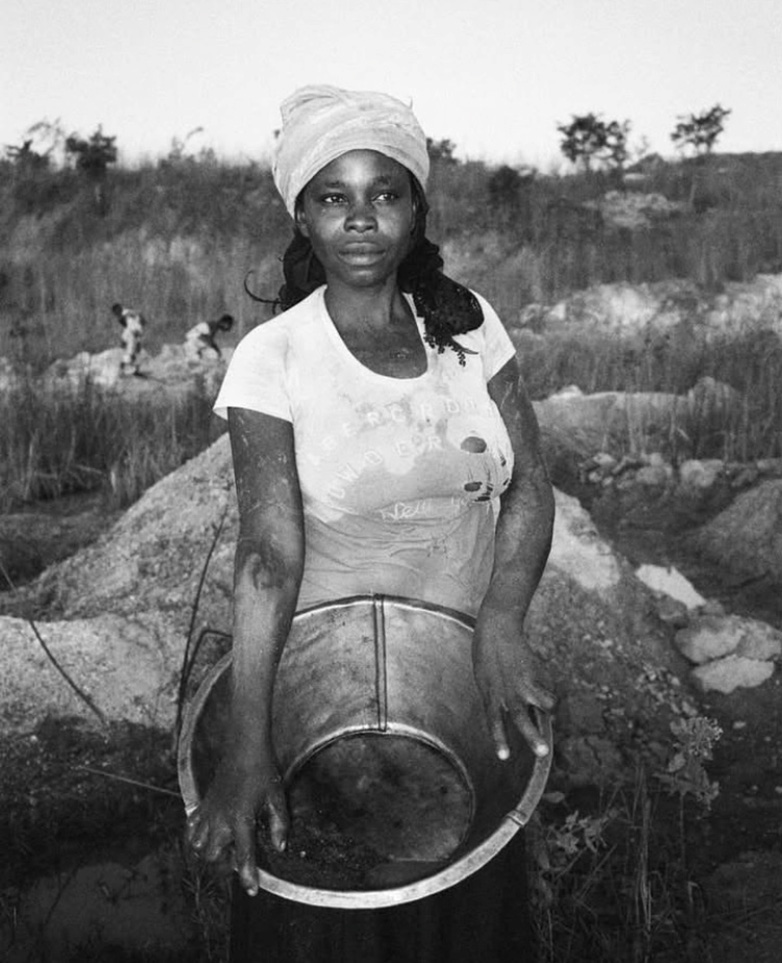

In 2022, he was detained for six days by the government of the Democratic Republic of the Congo as he sought to expose the devastating impact of cobalt mining on the health of local communities and the environment. His articles were published in The New Yorker, where he has been a contributor since 2014, and in The Nation.

As a result of these investigations, in November 2023, he was invited to testify before a U.S. Congressional committee to present his findings.

In March 2022, he visited the makeshift production studio Kraina in Ukraine, documenting how its staff continued broadcasting amid the chaos of war. His work on The New Yorker Radio Hour earned him a 2023 Edward R. Murrow Award.

On New Year’s Day 2025, he was in Damascus, reporting on life in the post-Assad era.

Nikolas Niarchos is a relentless and courageous investigative journalist whose work has been described as a model of responsibility. With precision and skill, he achieves a delicate balance that allows readers to confront and experience responsibility while remaining connected to the people affected by their actions—or inactions.

Okay, no, I think everything is fine. Yeah, the recording is working. So okay, I will start with an article from the New Yorker.

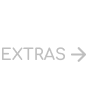

It’s the “A Sensual Dinner for Renoir’s Nudes” published in May 6 in 2019. So I think this article was the last of its era, right? Because since then you’ve made a 180 turn to focus on investigative journalism. And I want to ask, how did this happen? Like, what was the stimulus? Was it when you covered the Djibouti civil war in Yemen? The trip you made with your brother in the mines of Zuerat in Mauritania?

So, look, there were two things really.

I mean, I do like food, and I do like cooking. And I think maybe that’s part of my Greek heritage as well, a love of food and coming together as, you know, friends, family, and so on. And so I’ve always found it very fun to write about that kind of thing.

But the Renoir piece, sort of came about because of a friend of mine who works in the art world. And she basically suggested it to me. And I explained it to the editor and the editor said, listen, that sounds very fun.

But no, I’d love to be writing more about art. And I do write a little bit about art still. I recently wrote the catalogue entry for an artist friend of mine, Jill Mulleady, M-U-L-L-E-A-D-Y, who is a Uruguayan artist.

And my partner, well, my fiancé, is an artist as well. So I like writing about art. I like writing about food.

But I have always felt this kind of strong push towards investigative reporting and sort of reporting about conflicts and complicated situations. Because I think that, you know, you see this very distilled version of the human experience through those complicated situations. And to me, it’s very interesting to understand the different decisions that people make when faced with those kinds of situations.

It is, you know, wonderful to write about creativity. And I wish I could write about art all the time and so on. But I feel this kind of sort of push towards focusing on those kinds of situations.

And my god, when did this start? It started in 2015, when refugees and migrants were coming across the border into Lesbos.

Oh yes, I have a question about that.

I was visiting my father in Greece, in Spetses. And it was a holiday from work. And, you know, this is happening.

And I sort of called my editor and I said, Listen, I’d like to go out there. And that experience sort of led me to write about refugees and migrants in Europe and in Africa, actually. And I started looking at other refugee crises.

And I think it also goes back to being Greek and being part of the diaspora and so on. You know, my grandfather had to flee Greece, or he fled Greece during the war. And I’ve always thought that that’s a very important part of his story.

And then I sort of began reading Seferis, who was also, you know, displaced to Egypt during the war. And obviously, those experiences were very different. And I was trying to understand what the differences were between those situations and the situations of, you know, Syrians in a modern civil war.

And then, I think that journalism can have this amazing power. And it happens very infrequently. But, you can reveal truths and hold people to account.

But I think that the general voice of people writing these stories, has an important role in democracy in the systems that we live under, which is scrutiny of people in power. So it’s this sort of connection between, you know, these very, very specific instances of human experience and these very distilled and powerful moments for people. And also, this is kind of like hopefully helpful, hopefully thought provoking, and perhaps at some point, you know, revealing.

No, but I think that you have shed a lot of light into instances that are not actually covered by the media or, you know, the Western perspective. So I think that is really important as well.

Because I remember reading an article of yours where you were talking about your experience in London and how you were doing an internship. You learned about the Mau-Mau massacre and how the Western perspective did not mention that throughout your whole education and that this really bothered you. So, you know, I think it’s really important what you do and how you try to inform the people about things that might seem to be far away from us but actually affect us in many ways.

Yeah, I mean, that, well you try. The Mau story is interesting. And, you know, I wasn’t the first person to come to that story.

I think that Caroline Elkins was the first sort of scholar to revisit it. And it’s just interesting, like, this sort of tension between telling a story, and the people who’ve lived it, and sort of how a story gets out, and who gets to tell the story. So, I always try and be very aware of that, because, you know, I’m somebody who is relatively, I mean, I’m sort of a privileged person coming into these situations.

And often, you know, people do not understand how to tell their stories, but they want to tell their stories. And that, to me, is quite powerful.

So yeah, I want to ask , you have reported on so many instances, for example, like the Boko Haram in Nigeria, the abuse of women in Yemen. I’ve read that you’ve been six times in the Congo denouncing the nightmarish effects of, you know, cobalt mining, and its catastrophic events on the environment. So, I want to ask, because these are some very peculiar trips.

How much preparation time do you need? Do you have a team that helps you prepare, or let’s say, form a rudimentary travel plan before you go there? Or do you say that it’s more, it’s a more spontaneous procedure?

I don’t have a team. I think, you know, sometimes I’ll join along with other teams. For example, I went to Sudan recently, and a lot of the preparation there was done by Human Rights Watch, because I was shadowing what they were doing.

I was following their work. Yeah, I don’t really do it all myself. Because I think it’s important to sort of immerse oneself in these stories.

But sometimes things come up very quickly. Like, for example, I went to Syria the other day. And that was really, there was basically no preparation at all.

I mean, I spoke to a bunch of journalists, and I know who had been there. And I said, Listen, is it safe? Is it? You know, good time to go that, kind of thing? Where should I go? And they, you know, somebody gave me the number of a driver, I got in touch with the driver.It’s very dependent on each story. I would say, for example, when I went to Congo for the first time, I prepared for a couple of weeks at least.

But it was lucky because I had just finished my job at the fact checking department. And I was sort of, I had some time to really prepare that. But oftentimes, you know, I’m just, I’m just sort of pushed into something and opportunities arise.

And you sort of have to take them, for example, the Boko Haram story. Sorry, I don’t mean to go through every single story. But the Boko Haram story, I spoke to, I got a call from a photographer who I know who lives in my neighborhood, New York.

And he said, Listen, the UN has just asked me to go out to write about Boko Haram next week. Would you like to come? I said, Yeah, sure. So it was that kind of thing, you know, and I try and collaborate as much as possible with people.

And, you know, in that case, the UN had organized a trip and I was just sort of tagging along on the trip. But yeah, so it really depends on the situation. Just as a footnote to that, the best reporting trips are the ones, obviously, that have the most preparation and I’ve managed to get the most context and so on beforehand

I understand. So, you’ve talked about the Congo. And one of your articles that really stuck with me was the dark side of the Congo’s Cobalt Rush, right?

So not my title, just to reinforce, I didn’t like that title very much, because I think dark has the wrong sense in that point.

In what way, if you don’t mind explaining?

Well, I don’t know. I just think it’s like people think of this like the heart of darkness. And like, people talk about like, there’s this idea that like, Congo is this dark country in which like, nobody can understand what’s going on, so on. I don’t think that’s true. I liked the print title, which was Buried Dreams, which was also not my title. I’m not very good at coming up with titles.

But I thought that was a really, really good piece, a good title, because it had two meanings. It was like, you know, firstly, the dreams are buried, they’re digging, they’re looking for them. But also, their dreams of building a better country are getting buried underground, because of this sort of complicated situation.

There is this sort of contrast that has a powerful connotation to it.

Of course. But what I want to say is that like, while you were there, you spoke with many people, I remember the baker Zanga Muteba, the causeur Kilanga, and his partner, the 15-year-old Ziki. I want to ask, how did you manage to gain their trust and make them feel free to share all these things with you? How do you find the common language or, I mean, not only to communicate, but also to find common sense, you know, because you talked with some people like Emputu, who attributed the deadly explosion in the mine to the dragon’s flame. So, you know, these are people that have experiences and an approach to life that’s quite different to yours. So, how do you manage to communicate and be on the same page with them on certain things?

Yeah, that’s sort of what I was trying to talk about a little bit earlier, is that these people have very, very different experiences of life, this very sort of distilled experiences.

And obviously, you know, with the dragon collapse that had remained etched into people’s minds. And it’s funny, because you bring up two people, Odilonka Jumbaka Kilanga, and Trezo Emputu. And basically, I met them both at the same time.

Trezo was very open and chatted away and was sort of easy to talk with. Odilonka, who actually had a better way of telling his story and is actually the main character in this book that I’m writing now. He was much more reticent.

I think you must find the way that people are speaking, and the way that people are thinking about things, and trying to get into their way of talking the language, try and understand how they describe certain things, and how they’re thinking about stuff. I met them on my third trip to Congo. So, I was prepared to talk about those kinds of things.

But I found that my interviews with Odilon, for example, got better and better. And, you know, I interviewed him two more times. Yeah, three, three times in total.

And then I had, because I’m not allowed to go back, I had somebody else go give him some questions. Every single time that I interviewed him, you know, I understood him more and more. And we were able to have better and better conversations.

But obviously, their experience of life has been completely, completely different to mine. So it’s a situation of listening, learning, thinking about the way that they talk about certain things. A lot of that thinking about that came from a class that I took while I was a journalism student at Columbia with a New Yorker writer called Nicholas Lemon.

And, and he basically would set up these sort of fake interviewing situations, in which you would have to interview somebody about something very complicated. I remember I had to interview somebody about a new programming language. He had these people, these students from the acting school who would come, and they would be very difficult with you, and so on. And I think part of his point was, learn the language, learn the way that people think about these types of things. And there was a very good example that he used.

He had these two students sit, come and try and interview him. And he said, okay, I’m a hipster, which is like something that’s not too far away from any student, like there are hipsters everywhere in New York. I’m a hipster, interview me about my neighborhood.

And these people were like, you’re a hipster. What does that mean? Then he surprised them by saying “no, I resist the label of hipster”. And they’re like, no, no, you’re a hipster, like you’re obviously a hipster.

And he was like, “No, I resist it. Like, I’m not doing this interview.” And it was interesting, because the lesson in that is, maybe people don’t see themselves as hipsters, or they don’t see themselves as criminals, or they don’t see themselves as whatever, and trying to understand what they’re, you know, what they’re doing, and how they see themselves is really important.

Interestingly, with the causeurs, is what made it sort of easy is that a lot of them are really quite proud of being causeurs. So they see themselves as part of this kind of like, heroic profession, and even if they hate the profession, they are also find joy in this mythology around it. And so getting into the mythology about it, and talking about the dragon, and these sort of things, they start opening up, and they start telling you things that they might not have told you, if it was just like, “Oh tell me about cabins, or like, tell me about the time that the bad spirits came into the tunnel and that kind of thing.”

There’s this, there’s this quite special language to being a causeur. But at the same time, people like to talk about it in a weird way.

So, if I understand correctly, letting people be in their element while talking to you can help them be very productive. Maybe that’s the takeaway.

Yes, I think linguistically being in their element, and then there’s a whole thing about setting and whether there are other people interfering and stuff like that. That’s a whole different thing.

It’s like, if you look at human rights interviewing, what they’ll do is they’ll take somebody away from a refugee camp, set up a little tent, and or set up an area where somebody can come and sit and have quiet and space, and it’s only you, maybe a translator in there, or if you speak their language, just you and them. And you have these kinds of one on one, very direct interviews. And that, that technique, there’s a very good book about this called The Good American by Robert D. Kaplan, about the life of a guy called Robert Gersony, G-E-R-S-O-N-Y, who was reporting on human rights reporting for the US.

Well, I think he started for the USAID and then worked for the State Department and various other things as a contractor. And he developed this technique of reconstructing, you know, events of human rights abuse through intense, and many, many, many interviews with people in these very specific circumstances, by asking leading and non-leading questions, and so on. I think what I do is very different, because, you know, you’re asking people about how they felt, how they experienced certain things, in a way that’s different from a human rights interviewer, who, in the end of the day, wants to know, like, how many troops there were, what uniforms they were wearing, what did they do, that kind of thing.

But for me, it’s important to understand, like, how people went through a specific experience.

Yeah, instead of making it look like an interrogation. Okay, I see.

Well, you’ve, you’ve also experienced the degradation of human existence. And I want to ask you, like, when you come across people who have been through a lot of traumas, for example, I will mention Rima, the brutally abused 15 year old girl, who told you that she wants to study medicine, I think it was in Yemen. So, when you’re sitting in a room with this person, and you’re having a conversation, and you know how much they’ve been through, how do you manage to embrace their dreams? Do you embrace their dreams? Like, for example, her dream of studying medicine? Or do you advise her to follow a life course that better suits her experiences, or her current circumstances?

Um, so, again, this was another, another interesting lesson that I learned in journalism school; you know, as a journalist, you’re not supposed to tell people what to do, or give people advice and stuff like that. Especially when dealing with Rima, that was an interesting situation, because she kind of wanted to tell her story. Her parents, well, her mother wanted her to tell her story, her father was kind of unsure. So, it was really a situation of just sitting there and waiting for a long time, as she kind of, as both of them kind of came to terms with what I was doing.

Rima herself, she was quiet, she’s quite eloquent, but then she would stop speaking for a bit. And then, you know, she’d been through a really horrific situation. But no, to be honest, it’s not your job to tell people what to do, because you don’t understand their lives and it’s not like they’re friends or you are a professional giving advice, you’re not a lawyer, you’re not a doctor. And in fact, you’re not trained as a doctor. You’re not trained as a lawyer. So you might be giving them the wrong advice.

So, the best thing to do is to sit back and say, listen, tell me about these things, tell me about what you’re dreaming about. And I think it’s quite useful for people to speak about things and to unburden themselves. Oftentimes, you know, people will start talking about what they hope to do interviews where they’re reliving traumatic things.

And you can see that, like, by talking, by reliving those experiences, they’re able to process their own lives better, and they’re able to kind of think about a better future. Then again, like, I am not a psychiatrists trying to cure people, I just want people to have the opportunity to tell their own stories, in their words, and to not reduce them to just statistics and numbers and so on. And, and then there are people who don’t want to talk, and they are sort of shut down.

And then there’s the also the weird in between, which is when somebody comes up to you like “yeah, I really, really want to tell you a story that’s happened to me the other day, really want to tell you the story”. And you’re like, “okay, great”. You start asking basic questions and they’re talking, they’re talking, talking. And then there was a lady who I met in a refugee camp in Sudan.

And she said “oh, I must tell you about all these terrible things that happened to me, like, it was so bad to leave my home.” I said “Okay, tell me about leaving your home.”

She shared, all the bad things that she’d seen, she was from, I think she was from Kosti, which is a city in central Sudan. And, and she had had her home bombed. Also, she had had a problem with her husband.

She started telling me about the problem with her husband, without hesitation. And I said, “Oh, how did you get here?” And she said, “Well, I came in a truck.” I was like, “but can you describe what happened to you as you got here?” And she took me step by step.

She was like, “Yes, I was in this place. I was in that place.” And then suddenly, she completely shut down. She basically started talking another language. And my translator was completely confused. Because he said, “look, she’s gone from speaking something that I can understand to something that I just don’t understand.”

And she refused, and she was refusing to talk. And I found out that she had been attacked and sexually assaulted on the on the road. So, you need to understand that people want to tell you certain things, and they don’t want to tell you other things.

You must be very, very respectful of people. You know, when it’s pretty clear that they’re, having some sort of PTSD. In that case, I just said “Listen, like, let’s just talk about happy things.” And we just went back to, you know, talk about nice things and that sort of calm her down. The next day her brother came up to me like the next day. And he was like “Oh, you met my sister, I want to explain the whole story.”

And he was like, this and this and this had happened. And he had also been through something similar, which was terrible. But funny enough, he was very good in talking about it.

It doesn’t split usually down to gender. It’s just that some people have processed things better than others. And it depends on time, it depends on, you know, your mental state, depends on what happened to you and so on.

Okay. I mean, yeah, it’s good letting people tell their story, but keeping it respectful as well, because most of the people you meet have also been through some really bad experiences. I understand that it’s not always easy to ask them these questions. So, I am coming back to the article about the DRC. I know that the Congress invited you to speak about this truth in November of 2023. If you don’t mind, could you tell me a little bit about your speech, which was about the unrestrained mining of copper and cobalt ores?

Yes. I had been asked to speak about the environmental impacts of that mining.

It’s an interesting format, those seven testimonies, because it was a Congress, Senate, it was a joint committee. But basically, I think it was a House committee. They said, “you have X amount of time to talk about certain things, blah, blah, blah.”

They got in touch with me, they did a hearing, and they were very, very easy and direct to deal with. However, they did not give me very much time to think about these things. Luckily, it’s a subject that I know very well.

Basically, you write a testimony, and then you read from that testimony. And that experience was another instance of learning how the US government works, which was always fascinating.

So, you told me that you have been to the Congo six times.

You’re no longer allowed to go back there, right? I read that the Secret Service arrested you in 2022 and that you were detained for six days. Of course, I don’t want to ask about how this experience was because I’m guessing it wasn’t the best, but did you have contact with lawyers or embassy representatives and what was the dominant feeling? Did you think that you were going to be released quickly, or did you think that this was your midnight express in a way?

No, I’m really happy to talk about it and it’s not something that’s traumatic or bad or something that sort of sits in my mind as a big block. Did I have access to lawyers? No, it was not an arrest, it was arbitrary detention. It was a use of government force to stop journalists investigating and to intimidate both myself and other journalists into not investigating specific allegations around the president’s family and various different separatist militias.

How long did I think it was going to take? That’s a good question. For some reason, in the back of my mind, I had this sort of idea that it would take up to 18 months, but it was only six days in the end and I was very glad that I was out. That said, there were interesting sides to that because the Congolese secret police were very chatty, so I found out a lot about the Congolese secret police.

So, you gained insight while being inside the prison? ( laughter)

Yeah, I feel like every time I chatted to somebody, and everybody was kind of bored. We got really revved up at the beginning and then they realized that I wasn’t really a big threat and they kept saying I was a spy and I was just like, kept making jokes. As long as you humanize yourself as much as possible, that was my first thought, just make them see that you’re a human, that you’re like them, that you have a family, a girlfriend, a life, whatever. And by the end they were telling me about their mistresses and how they were annoyed; one guy had to buy jewelry for his girlfriend but his wife had found out and blah, blah, blah.

It was just like a soap opera. I’m not trying to reduce how serious and how there were some really scary moments, but these people were living these really, really unsustainable lives. One guy wouldn’t tell his neighbors what he did for work.

He didn’t want his neighbors to find out what he did for work because they hated the services, and he was worried that people were going to come in and kill him. So like, he pretended that he worked as like a bureaucrat somewhere else.

Now, in terms of consular assistance, I was there on my American passport. My American passport was the one that, you know, that counted, I guess. Or at least that’s what the Greek consular said. And, and basically, while detained, I was able to pass two notes, and they transferred me on a commercial flight.

So, I was able to pass these two notes to, to two different people who I didn’t know. And I just wrote, this is my name, this is my passport number. I’m an American passport holder. Please, drop this off for the embassy if you can”. And to the amazing credit, I mean, it’s really the kindness of strangers that overwhelmed me. They both went to the opening time of the embassy the next day.

And the embassy called up the Congolese secret police. And they said, well, we’ve received these two, two communications that this guy is, is arrested and we have data saying that he is missing. And they knew that I was being held because they had my notes. And the Secret Service were like, “oh, no, we don’t know, we don’t know who that is.”

So that was that was that was also bad, because that becomes enforced disappearance at a certain point. Regarding my friends and family, it took them a day to acknowledge that they had me and everybody was scared. They thought I was taken by the militia and so on. Making them worried was one of the things that made me really upset, the most upset because I understood that I was okay for the time being. But they obviously had lots of bad images going around in their head and so on.

Okay, yeah, like the idea of not knowing where you are, they can only think of the worst just because they’re worried about you. So that must have been stressful.

So, I want to finish up with the Congo chapter. But I have one last question about this. I want you to tell me, do you think that if the Nobel laureate Dr. Denis Mukwege had been elected in the 2023 presidential elections, would that have been a good thing for the Congo? Would he change anything towards the best?

Look, I don’t know if Mukwege had the means, I mean, this is my own analysis.

I don’t think he had the support and the party infrastructure to properly win that election. And he certainly did not have a party infrastructure that would allow him to effectively govern quickly. I think he’s a great guy. He’s amazing, what he’s done is incredible. I thought his book was incredible. And I reviewed his book for the New Yorker in an unsigned review.

I respect the hell out of the guy. But he announced his candidacy way too late. And I think that spoke to the level of preparation that he had done for the campaign.

And I’m all for doing things at the last minute. I do things at the last minute the whole time. But I think that kind of decision is something that you must really think through and build up a coalition and so on.

You know, there are real questions about what would have happened if the results of the 2018 presidential election had been respected, and Martin Fayulu had been returned to the presidency. But the fact is that you have seen what is essentially a very, very corrupt, kleptocratic regime which uses arguments to oppress people which really, really annoys me. It’s like using these arguments about genocide and colonial responsibility to allow themselves or to help themselves to the great riches of Congo. And while they’re doing so, everybody’s poorer. And they have also sparked a civil war, which is just getting worse and worse now in the East. And, you know, in the end of the day, the Congo really deserves a better government. They deserve a government that is able to rule effectively and efficiently without lining their own pockets. I mean, in a way, it’s not dissimilar to Greece. But, you know, it is even more frustrating in Congo because it’s been such a tragic history for so long.

Yeah, so you talked about the corruption of the current regime. I would like to ask you about fact-checking in this case because I watched your video from TEDx, the one you talked about this topic. I think it’s clear that social media has complicated the reasons why the current government should leave. Unfortunately, this narrative is also repeated by news outlets, because fact-checking over there is non-existent. Do you think that people fall in this trap of misinformation because they’re ignorant? Or do you think that there is another reason that this current regime perpetuates?

Well, a couple of things. Firstly, I mean, to call, I mean regime might have been the wrong way of describing because it is a government is; maybe the election was incorrect and so on. But at the moment, he’s not, you know, he’s not a dictator. But going to this idea of fact-checking, is the government an honest broker in terms of information? I think that’s absolutely a key question. And I would say it isn’t.

I think there are many, many people who want to push certain narratives. Social media complicates everything. And, you know, is fact-checking possible in Congo? Yes, absolutely.

We’re able to check my pieces very easily. Not very easily, but you know, there are complicated things that one must deal with. It gets a little bit confusing sometimes, because there’s lots and lots and lots of misinformation.

And that’s what’s interesting about Congo is there’s just this avalanche of misinformation that you see coming through in certain books. But you know, sometimes people will go there and listen to all the rumors, rumors, and then just like, put together reports based on those rumors. It’s difficult to get documents in Congo, but not impossible. And there has been, especially with mining, there has been a lot of initiatives to, or there’s this one specific initiative called congomines.com which has digitized a lot of the Congo mine records. So, you can go back and check people’s statements.

So, you know, you must be careful about what you check, and you have to be careful about making sure that things are correct, but it’s not impossible. To go back to the question of social media, what’s very interesting is that I had a conversation with a news anchor from CNN the other day, and she was saying to me, “listen, back in the day, television used to be the medium of the masses, and it was, you know, quality television was checked and so on and so forth. But now social media is this kind of mass media, and that is absolutely not fact-checked, and it’s absolutely not scrutinized before publication in so many instances.”

So I’m, you know, I’m worried that people believe things more and more on social media, and I think that the Israel-Palestine conflict that has been raging since the 7th of October is actually a very good example of that, because you have received through your phone, or I assume you have received through your phone, raw, unfiltered stuff that is being used by one or the other side as propaganda, essentially. And I think that as a journalist, you learn how to deal with that and think critically about it. But, you know, an 18-year-old waking up, you know, first thing in the morning, they see something that comes basically directly from quite a sophisticated propaganda organ, and they are inclined to believe it.

And then algorithms push more and more of that kind of video or, you know, speech or whatever it is at you. And suddenly, you’re stuck in a sort of hole of not being able to see the other side. And I think that that’s really, dangerous, because you do not have any balance in the way that you’re approaching things.

That was actually my experience too, because, like, when the whole conflict began, I woke up one day and my Instagram was filled with stories from my classmates. And, you know, not all of them were supporting the same side, but it was just stories that were coming from the same and same sources. I didn’t know if there was any objective evidence in the background, but it kept coming through. I think this forces a narrative that might confuse you than reveal the truth.

Yeah, exactly. And it’s really frustrating to people who are not versed in this stuff. And you just throw your hands up.

So, there is a Greek proverb that says, “teacher, you teach, but you do not keep the law.” In Mauritania, you ask Omar if he realizes how dangerous an upcoming trip is. And he says that he leaves it to God’s will. To be honest, I laughed because I was like “look who’s talking.”

So, I want to ask, is there a voice that points out the dangers to you? And have you heard it? And in what cases?

Yeah, I mean, I think, like, you’re always taking calculated risks every time you walk out of your front door. And I’ve seen friends of mine who have never lefttheir home cities, taking far more risks than I have ever taken. I know what you’re saying. But in a way, you must be thoughtful about what you do. And you must be careful. And if you’re going to a very dangerous situation, you have to prepare yourself. I don’t think I take unnecessary risks.

And I think I’m careful about it. I make sure that if I am going to a very risky place, I have proper security, or I will speak with security consultants, or travel with an organization that has proper security, or that kind of thing. Obviously bad things can happen.

If you only think like that, then you, you know, you actually miss out on the information. You miss out on life. And you could, I mean, spend your life trading Bitcoin and probably be a model trader. And I know people as well who anything in their lives have basically not done, because they have just sat around, waiting for, you know, the perfect moment, or the right job, or whatever it is. And, in fact, they end up just sitting in the same job that they were in, you know, 10 years ago, and they’re not very happy about it. So, I think that there’s a lot to be said for just sort of taking opportunities as they arise.

Okay. So next question. Is there a topic you wouldn’t cover a report on, no matter how much you wanted to?

Um, not that I can think of, but I’m sure that there will be things that come up, would come up. I’m trying to think of things that I haven’t, stories that I haven’t taken. I’m sure there have been, but none really come to mind. Um, at the moment, I think it’s very stupid to go as a journalist to Iran. Because there has been ample evidence that they take people hostage in order to extort money from them. I was quite lucky when I was a student, I went for my student newspaper, I did something in Iran. But looking back on it, I mean, that was taking a risk that I didn’t understand.

So, you know, it’s a good, good lesson about understanding risks or mistaking. Okay. Um, so you’ve been to so many rather dangerous places throughout your career, especially lately that you’ve dealt with investigative journalism.

I constantly wonder what the psyche of a person like you is, like when you decide to go to Ukraine in the early days of the war or spend, the New Year’s Eve, to report from Syria. I have come up with many possible explanations, but I want you to tell me, like, I want you to describe to me, what is this flame that burns within you? What makes you do all these things? Because today, five minutes before talking with you today, I saw your post from your Instagram, from Syria. And I thought, “that’s a very special way to spend New Year’s.” (laughter)

I think basically, you know, the Syria thing was, was just about seeing history. My editor said, listen, we need a piece from Syria. I was very lucky to be able to do that. It is a great privilege to, to see history as it happens. It informs your way of writing and your work. It makes you better able to make those kinds of judgments. That I think is the reason for doing those kinds of things. Going to Syria, for example, was quite nice.

I mean, it was just, it was very positive, and people were happy that Assad had fallen. They were obviously very uncertain about the future and worried, but I don’t think it was a situation in which unnecessary risks were being taken and stuff like that.

Okay, moving on to some other questions. I’ve done a fair bit of research to find out whether there is a gene that enables people to be risk takers for altruistic purposes. Would you say that you have that?

I don’t know. That’s a question for scientists. But I think that it has to do with calculated risks and not being reckless. And I think that, you know, one of the risks that I feel most acutely in my life is, is actually sort of sitting in a situation where I miss out on doing things because I am scared of every detail. It might be something to do with my upbringings in Greece. There was always concerns about various different groups that had, you know, political agendas, and so on. For example, we were never allowed by my father to go to Athens as children.

Of course, in life, you can take horrendous risks. But as long as you’re thinking clearly and carefully, and you don’t get stuck into a situation where you are, like, taking risks for granted, you can go to places and meet people and so on, in ways that are, that are perfectly safe and, and maybe safer than, you know, sitting at home and, and watching television.

I see. Okay. So, in the beginning of our discussion, you talked about the refugee crisis in Greece. As a Greek person, I have really lived the drama of, you know, the incoming waves of refugees. So, in Samos, you covered the story where you write down the facts about the refugee camps and what happens over there. But you don’t make the Greek reader feel guilty. I think this connects with a comment that a professor from Vanderbilt University, Paul Kramer, made about you. He said that there is a thin line between engaging the audience and attributing responsibility. So, I want to ask you, how do you maintain this balance? Like, how do you form your text in this manner to achieve this?

Well, I mean, I think that, like, generally, I don’t think it’s useful to make people feel guilty; that shouldn’t be your aim.

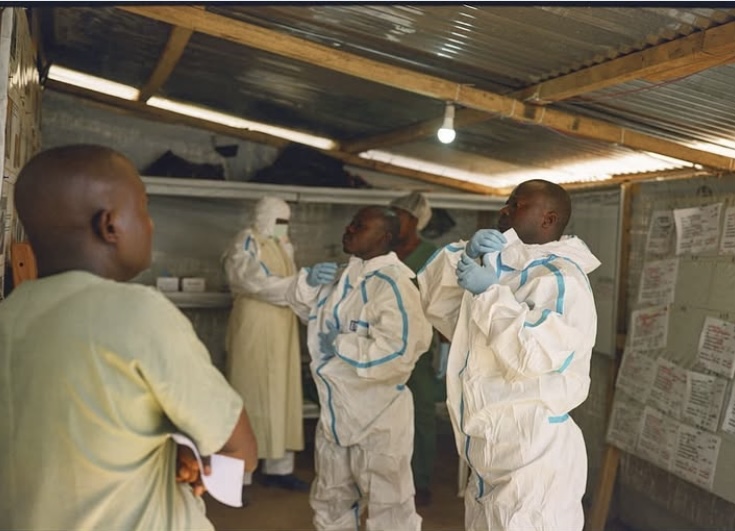

As a journalist, you’re trying to inform people and trying to help people make better decisions. And, you know, the Congo story is interesting because everybody in the western world has an iPhone in their pocket or Samsung or whatever it is. Those phones have minerals that come from, you know, a very, very complicated supply chain, to put it lightly.

And you know, we’re all kind of responsible for these things. But I don’t think the solution is to not use cell phones. Maybe we should organize to raise more awareness.

Or you know, benefit the people that provide us with these materials than actually living in prosperity while the others suffer to provide them.

Exactly. And I think, you know with Greece specifically, I always thought Greece had done a remarkable job at trying to welcome refugees and migrants. Local governments, for example, like the mayor in Lesbos was, was incredibly supportive of initiatives to try and create new camps and bring water to certain areas and so on. But I find that at the end of the day, it’s not about making, you know, everybody feel guilty. It is about holding people in power to account and, and making people think more about their roles, you know, in a democracy. Making people maybe more attuned to the struggle of the people that they might see on the street and so on.

I actually think that Greece did a sort of heroic job and in trying to welcome people. Yeah, because I think what’s important to mention here is that we welcome more people than we were able to help. Like, I’m not saying that we do not try to help them. But when you have so many people coming in here, it’s not always easy to take care of them.

Okay so by doing all this, your work has received many awards, but I want to know from you personally, which of your articles do you consider to be the best written or let’s say, the most influential, besides the one about the DRC?

I mean, I hope that every article has been influential in its own way. You know, even things that I used to write about restaurants in New York, once I wrote a piece about a Somali restaurant in New York, and it was a sort of mom-and-pop restaurant that had opened on 116th Street. And, and I wrote this review and suddenly, when I came back to the restaurant the next week, it had so many clients, so it was a testament to the power of The New Yorker. They had hired more people, and were able to renovate the restaurant and stuff like that. I got quite happy about that kind of thing. Because I actually saw the positive impact of my work, let’s say, and it was done with immediate effect.

I think my work on the Western Sahara was good and comprehensive, and, and certainly helped focus the debate in the circles of Washington, and then in Paris, and things like that.

I’ve had many people who, like, work in foreign affairs, come up to me and say, oh, you’re the person who wrote that article, like, we use that in our briefing pack, that kind of thing. So that’s quite good.

The Congress stuff is, I felt… I think one of the, the one that refers to Europe as well, I think the one about the statues in Ukraine, and how people cover them up to protect them from the bombings were powerful too.

Yes, I think it was symbolic in its own way. Because yeah, that was an attempt to try and get people to think a little bit about, you know, the effect of war on things that were not military or refugees or whatever. And I was happy with the way that it turned out. I think that was, funnily enough, quite well received in the US. Hopefully it got people to think about things in a more specific way. I think so.

So, to talk a little bit about the environmental crisis and climate change. Have you ever been at a COP conference? And if so, or maybe from the things that you’ve read about these conferences, do you think that the decisions being taken there are actually helpful in tackling this issue?

I’m not an expert on this, so sorry, I can’t give you a good, informed response. I’m sure there are many good decisions that are made at conferences like that. I have never been to a COP conference, and I would be very interested in doing so. But it’s not my main priority, because I think that, you know, seeing things as they happen on the ground is more important. And there’s only so many minutes and hours in the day.

But yeah, I would love to go at some point if I’m ever able to.

About your new book on the “elements of power”. I imagine it is different than writing articles. Do you think it was more difficult writing a book because it requires more extensive analysis?

Yes, it’s a short answer. Look, writing a book is difficult because of the volume of information that you’re working with. If you want to be sort of definitive in a way that I’m trying to be in this book, you have to be meticulous. And then the head of England books came back, what we really want is a grand history of battery metals, basically. I thought God, I’m not a historian, but I’ll give it a shot. And, and that’ kind of what I’ve prepared.

But you’re feeling optimistic about its publication, right? And like, do you think that it will be translated to Greek as well?

It will be translated into Greek. I have signed a deal with a Greek publisher, but they haven’t put anything out about it. There will be some events in Greece which I’m quite excited about. It will show everybody how bad my Greek is.

You said that you felt like a historian working while working on this. I want to ask you, would you ever consider writing about, like not becoming a historian, but would you consider analyzing history as part of your work?

Yes, and I think I do it already. I mean, I’m not sure if I want to become a historian because it’s not the only thing I want to do, but you know, there’s this kind of journalistic history that requires working with primary sources and stuff like that. I love doing that. I am searching through documents and letters. I’m finding a way of telling a story, which is engaging. You know, Patrick Radden-Keefe, who has been a great inspiration to my work. He, for example, wrote the history of the Troubles in Northern Ireland through these tapes that had been collected by oral historians at Boston College. And that was really, that was really both a journalistic book that had real characters who were moving around the world in a way that, you know, journalists would, but also a work of history because it was based on historical sources.

So, do you think that this in a way inspired you to combine history and journalism in a way for the book?

Yes. Like narrative history. Trust me, I think one day I’d love to write a book about ancient Greece or something like that, but I think it would be pretty different because, you know, we don’t so much in terms of primary source material, basically.

All right. So, two questions left. I understand why you have the photo outside the Twin Peaks on your profile. My interpretation is that because you find it surreal, like your life. But your Instagram username, a postcard from a volcano, what is it about? Like, is it the Nyiragongo Volcano in DRC? Or is it another symbolism? Or do you just like the idea of this name?

So Twin Peaks has been this kind of like, amazing inspiration and it’s sort of like this very moral piece of filmmaking and artistry. And David Lynch, who just passed has always been an inspiration to me. His book, Catching the Big Fish is really an amazing book about meditation. But also about retaining thoughtfulness and mindfulness in a way that’s not too light. He engages with this kind of like mystical and, and almost magic world. And also dark aspects of the human psyche and so on. So I think that’s like, that’s, that’s always been inspiring to me. And this is the Red Lodge and the Black Lodge, also White Lodge and Black Lodge.

Postcard for the Volcano is a Wallace Stevens poem, which is about ageing and has various contrasts between this New England houses. And there is this connotation about a dirty house in a gutted world. A tatter of shadows peaked to white. So, this movement between light and darkness, which I’ve always been very interested in, amazes me. Stevens for me is one of the greatest American poets.

Okay. And so last, the last question is about your F6 Nikon camera, because I know that you’re attached to it. And I’ve read that you took the picture of Obama just before he was elected president. If I remember well, you weren’t, you didn’t actually have permission to be in there, but you went in there as a college student. I found it really fascinating. What is it about this device that has been with you know with you for your whole career?

Yeah, I’ve had that F6 for a long time. I sort of like hold on to all these old cameras and things. It’s not crazy expensive but it has been a great thing to have with me. But it at the end of the day it has started feeling its age. I bought it when I was 18. I think I got it for my 18th birthday.

And it was already a kind of old camera by that point. I bought it secondhand, and it is just an incredibly resilient camera and it’s very clear.

Was it the one you used in your latest trip to Syria?

I did not bring it with me to Syria because I didn’t know how weird people would be around cameras. And sometimes when you have a big camera, people get uncomfortable around it.

But yeah that Nikon F6 is a great camera and they don’t make them anymore. And, you know, they haven’t made them for a long time. All those F series are just incredible cameras.

So this, this was the last question. I really want to thank you for doing this and for actually giving me a one and a half hour, almost one and a half hours of your time. Cause you know, this project for me has been really, really important. I actually wanted to include a person with your experiences and, you know, like I came across your work like some time ago, and I first read about the DRC and I just thought it was inspiring that someone unveils these kind of truths and wants to share other people’s stories. So yeah, I really wanted you to be a part of this and now I’m really, really happy that they have this interview, you know.

Absolutely. With great pleasure. Thank you very much for spending the time and speaking with me. And, um, and if there’s anything else that you need, please let me know.

So yeah, what I want to say again is, thank you. Thank you! Thank you! Have a great day!

I listened to his stories, barely able to absorb everything he was telling me. I knew that his articles required focused attention, but I had assumed our conversation would be more easygoing. I was completely wrong—because in this case, I didn’t have the luxury of rereading the previous paragraphs. The anxiety of trying to ask everything I wanted only intensified my confusion.

But it wasn’t just that.

As I listened to his stories, a song by Hadjidakis kept playing in my mind—Kemal, the tale of an Eastern prince who rebelled but ultimately failed. The poem ends with the lines:

“Goodnight, Kemal, this world will never change.

With fire and with a knife, the world always moves forward.”

I was certain that this must also be the journalist’s view—he had so much in common with Kemal. I was wrong again.

Ten years in the most merciless places in the world, where life and death often have neither meaning nor distinction, and yet Nikolas Niarchos still believes that the world can change!

Nikolas Niarchos is an incredibly optimistic, passionate, kind, humble, and generous person.